“What’s Peru like?”, “are you from Lima?”, “how was your life like back home compared to living in Hong Kong?”. These are some examples of questions people ask me, either when we first meet, or after developing a certain level of friendship. A Canadian friend with a strangely expansive knowledge of Peruvian politics, recently asked “what do you think of Pedro Castillo (Peru’s former President)?”.

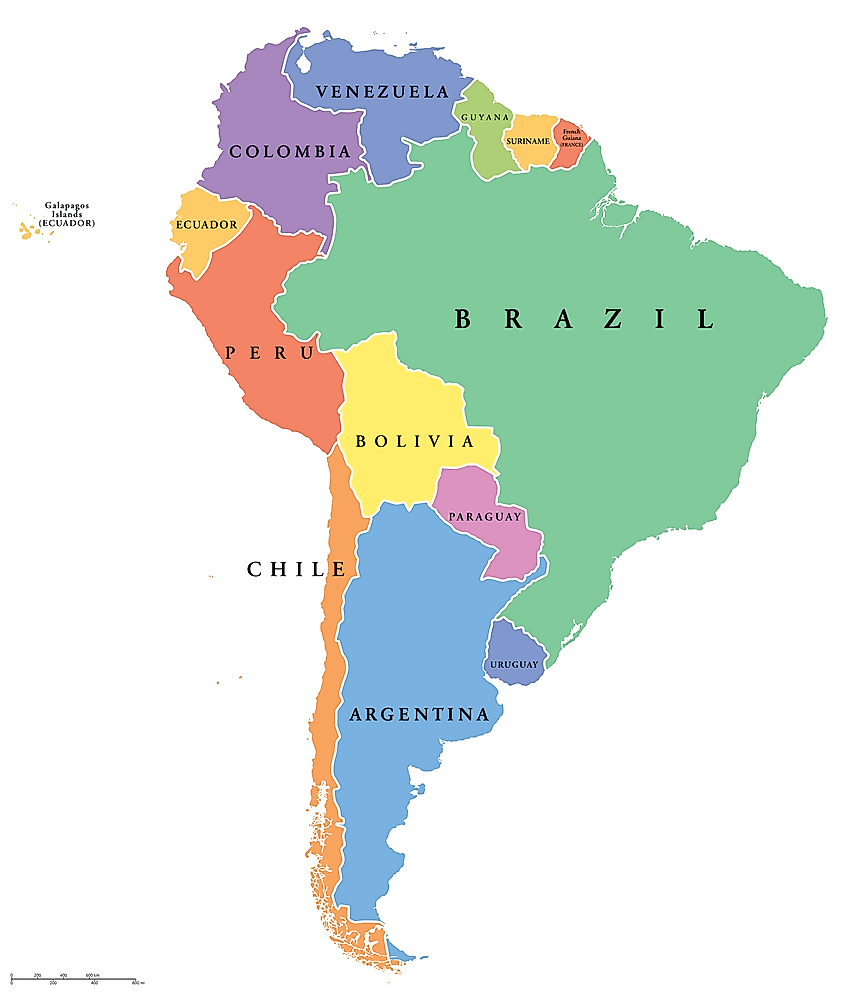

With only a couple of hundred Peruvians in Hong Kong1, people usually ask me to share more about my background, given the limited awareness of my country of origin in the region. To quantify this a bit more and provide you with some sense of the level of awareness, only about half of the people I talk to know Peru is located in South America. I usually tell them:

“Do you know where Brazil is? Peru is right next to it.”

They seem to have an idea after I say that, but you can take a closer look below, in case you are not familiar with our political map.

Source: Pinterest.

In this post, I want to share the key cultural differences between living in Lima and Hong Kong, having been born and raised in a developing country in Latin America and spending my more recent adulthood years in a developed city in East Asia. While I have encountered numerous cultural shocks and some discomforting experiences, the resulting acquisition of knowledge and awareness has been a natural and enriching consequence.

My first day at work

I was aware my colleagues were international, based on the information collected during the recruitment process. However, I did not have sufficient time to learn about the working environment in Hong Kong, nor anyone to tell me from their experience (especially from someone who had relocated from Latin America). I recall asking my recruiter to help me arrange my flight to Hong Kong at least one week before my start date. Luckily, I was given ten days to adjust to the time zone (13-hour difference), so at least I showed up well rested.

Flying across time zones. Picture taken on the plane.

On my first day at work, I remember going to the HR floor to collect a temporary employee card, which could not be used to access my department floor yet. I then headed to the 5/F, where my office was located, and noticed there was no 4/F on the lift control panel. I was told the story about the number four2 in Chinese culture some time later, but I originally thought it was an unfurnished floor that had to be built but not used to avoid bad luck. It sounds very silly now, but you can count that one as cultural shock too.

Meeting my teammates

After reaching the 5/F, I patiently waited outside the entrance for someone to unlock the door. I originally expected my teammates would pick me up and take me to my seat, but I was told they were in a meeting and that I could wait at an empty desk until everyone returns to their seats. I sat at my temporary location and waited, but nobody seemed to be aware of my first day at work. I felt like a stranger, uncomfortable, not even knowing where the toilet was. I saw some people going back to their seats with their notebooks, but nobody approached me.

I could not wait longer, so I stood up and asked other random colleagues where I could find my manager. Someone pointed at where he was seated, while I learnt they were not informed of a new joiner. I got a bit shocked but had to pretend it did not affect me. When I spoke to my new manager, he told me there had been a change, and that I was assigned to another manager, who was on leave. At that point, I wished I was 18,000 km. away back in my previous office in Lima, having a nice conversation with my old colleagues, who were my friends too. Finally, after a rough start, my new teammate Ace, who later on I became good friends with, walked me through the floor introducing me to some of my colleagues and facilities (pantry, toilet, entrances, etc.). I finally felt welcomed, but I was expecting more based on my experience working embedded in Latin American culture.

Greeting my first female colleague

I spent 2 years in my first job in Hong Kong, so I eventually got to know most of my teammates (around 40) over work meetings, lunch, and extracurricular activities. While I cannot remember everyone I was introduced to on my first day, I will never forget about the time I was introduced to the first female colleague. It was probably the most uncomfortable moment in all my tenure and it happened on my first day! Ace, who introduced us, said …:

“… {her_name}, this is Pablo from Peru”, …

… and I automatically leant forward to greet her with a cheek kiss. When I noticed she was not moving, I immediately realised that I was not following the office protocol, so I returned my upper body to its vertical position and shook hands with her instead. She played along in a very professional manner, and we proceeded to talk a bit about my background. She told me Peru is “on her travel list”, which is another example of things people tell me when we first meet (always glad to hear that from a stranger). We never talked about this uncomfortable situation, but I have shared this story with friends outside work. Generally, they are surprised about that way we greet people in Latin America, especially if they haven’t been to a place where that practice is common, so I explain them it is normal where I come from.

Language at work

Language was expected to be one of the main challenges after moving overseas. I remember I was completely lost with the first project I was assigned to, as my teammate handed me a printout of the latest deck titled “One-off AMH CLI”. I did not know the meaning of “one-off”, as I had not come across with that term before. The other two were acronyms to refer to the market we were working on, and the specific initiative, respectively. I should have been prepared to understand at least 33% of that title, but I got 0%! The other 67% would not have let me understand the whole context anyways. As it turns out, compared to Spanish, the use of acronyms in English is widely spread, especially in multinational firms like the one I worked for. I later found out there was an internal website that contains a list of the most used business acronyms!

As a result, I had to double the effort to get used to working in Hong Kong: switching from communicating in Spanish to English plus getting used to the acronyms used in a multinational firm (and in English itself). This part of the story only involves the first page of the deck mentioned above only, so I had to work much harder to understand the rest of the slides, and to get my job done by the end of the project.

Getting used to communicating in English

Outside of work, I did better in terms of finding new friends in town and communicating to different people, or at least I did not struggle as much. My overall English skills have improved over time in Hong Kong, although it was not easy at first, especially after realising there are so many different accents I was not used to listening. The English used in movies, TV shows, and news (i.e., the one I was used to) is quite standard, but there are many other styles you only learn after interacting with other English speakers (native and non-native). The truth is, having an active social life helped me improve my language skills, including picking up some Cantonese words and phrases from my local friends. I use to have headaches before going to bed though, given the extra effort my brain was putting to process all new information.

Hong Kong’s efficiency

If you ask expats what they like about living in Hong Kong, most of them will mention its efficiency compared to other cities. While salary levels are arguably the top reason why people choose to stay in this city, being able to get many things done in a single day is always appreciated, especially if you are an active person. The city is well connected thanks to the different transportation options available round the clock. Convenience stores are found everywhere operating 24-7. Courier services are speedy often delivering before the expected date, and the list goes on.

A good way to measure efficiency is the time spent in a specific transaction. I usually take less than 5 minutes from the time I enter a fast food restaurant until I walk out with my takeaway order in hand (except during peak hours), and less than a minute to buy a drink at a convenience store. Sometimes, the reason is automation: e.g., the existence of a self-service screen where you can place an order and pay with cashless methods, minimising human interaction that can lead to a longer waiting time. Other times, it is about the fact that people do not engage in further interaction beyond the strictly necessary to complete a transaction.

Straight-to-the-point culture

I stayed in the formerly always busy Tsim Sha Tsui for my first six weeks in Hong Kong. I use to leave my place in the evening and walk around the area just to see how people go about their business. One evening, I went out to the convenience store to buy a packet of cigarettes (more out of curiosity than being a smoker). I saw many new brands I was not aware of and I decided to ask the cashier for a recommendation. There was an awkward silence after I said “which brand is good?”. It might have been due to the language barrier, but I felt the pressure to make up my mind from two sides: the salesperson, and the few other customers waiting in the queue. I decided to pick a random one, pay and leave. In Hong Kong, you can feel someone is right behind you when you go to a convenience store or a supermarket, and people often put their goods on the cashier desk before you’re finished. I try to keep my distance, but it seems people are in a rush to pay, making personal space usually compromised.

After this experience, and similar others, I realised the city is efficient also because people go straight-to-the-point without engaging in unnecessary interaction. In Peru, you can usually have a casual chat with a shop owner when you go out to buy something (including the very first time you meet). This is not usually the case in Hong Kong, unless you visit the same shop a few times. Of course, it doesn’t mean that there is no interaction with people whatsoever. Staff who work at my residential building, for instance, are quite friendly. Likewise, tea ladies at the office are often chatty and try to engage in conversation in spite of clear language gaps. At the end of the day, it depends on the person, and the context. However, it is less frequent to find casual interaction with locals, compared to where I come from, even after accounting for language barriers.

Conclusions

While some of my first experiences in Hong Kong can be now considered amusing (e.g., trying to greet my colleague in a Latin American style), others still feel quite the opposite, since they lead to stressful situations and uncomfortable moments (sometimes even today). Language and cultural barriers are always expected, even if you move to a place where the same language is used, so there is not much you can do to avoid them, except giving yourself some time to adapt and close those gaps with practice. Regarding other matters, like the working environment, I believe your impression depends on where you come from. Some of my friends who have studied or worked in Latin America enjoyed how warm and welcoming people were. So, for me, coming from a “warmer” place, the contrast was (and is) sometimes less enjoyable. I do not intent to sound negative though. Quite the opposite, the efficiency of the city and the people (what I called “straight-to-the-point” culture), makes this global city an attractive place for me to develop my career, learn more about local and foreign culture, and enjoy an active lifestyle.

There are other traits that are not mentioned in this post, as I wanted to focus the attention on cultural differences. For example, how close nature is from the city (e.g., hundreds of hiking trails), the rich food culture, the quality of sport facilities, safety (specially compared to my hometown), its strategic location in the heart of Asia, just to name a few. Overall the balance is in favour of Hong Kong, at least as of today, as I approach my seventh anniversary living in this cosmopolitan city.

- Based on a casual conversation with a member of the Peruvian Consulate in Hong Kong. Not an exact figure. ↩︎

- In Cantonese, the pronunciation of “four” (sei) sounds like the one of “to die”. Hence, its use is avoided in different situations, such as numbering the floors of a building (not always though). ↩︎

Leave a reply to SK Cancel reply